Tears came instantly to my eyes when I heard about Seamus Heaney’s death.

Tears came instantly to my eyes when I heard about Seamus Heaney’s death.

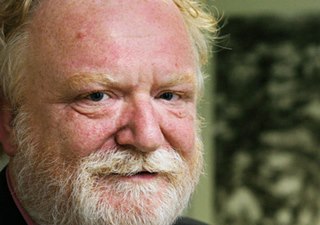

To many Ireland’s greatest ever poet – certainly the one who connected most with the ordinary folk who make up the majority of the populace – Heaney died at the age of 74 today following a brief illness.

I learned of it, as so many people learn of so many things these days, on Twitter. Someone posted a link that looked all wrong. “BBC News: Seamus Heaney Obituary” it read.

It looked all wrong. It felt wrong. I pressed the link, hoping and, if I’m honest, half-expecting it to have been caused by some unexplained kink in technology.

My immediate reaction, when I reflect on it now, a couple of hours later, was clearly one of grief. When the truth became apparent, tears sprang instantly to my eyes.

Since then I’ve been trying to explain it to myself. Why was Heaney so universally loved and cherished? Here’s what I’ve come up with:

– I never met him, but I felt like I knew him well.

– His smile was always warm; never was there a sign of artifice.

– His humility was always genuine; never, ever, was there a hint of conceit.

– His voice. Oh, we should be glad for the wonders of technology, because his voice can exist forever and a day. What an incredible voice.

– His clarity. Whereas a certain diligence or the aid of footnotes might be required for a spell with Yeats, Heaney seemed to speak to everyone. The potency of “Mid Term Break”, say, was immediately apparent to my eight-year-old self and remains undimmed three decades on. There was no obfuscation. Like Patrick Kavanagh, even more than Kavanagh, Heaney chipped the essence of existence out of the seemingly banal.

Heaney’s work touched so many, even those otherwise indifferent to poetry. That, the gift of cerebrally connecting with the masses, is surely one of the hallmarks of the great artist.

Looking at Heaney from afar, he never seemed to be interested in art for art’s sake. With him, it felt that art was life, and life was art.

The solace, because in art there is always solace, is that in his death Heaney will find thousands of new readers, and his words will seduce most of them too. Over half a century or so, Heaney has built an altar that will attract worshippers for many more half-centuries to come.

Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam dílis.

Here’s a montage of Heaney reading “Digging”, compiled as part of a BBC documentary a number of years ago:

There’s a full-page excerpt from Julian Gough’s recently published Kindle Single Crash! How I Lost a Hundred Billion and Found True Love, honorary Irish writer Molly McCloskey reviews a new book of essays on artists and writers by Janet Malcolm, Gabriel Byrne reviews Roddy Doyle’s new novel The Guts and there’s an extensive interview with Doyle himself by Patrick Freyne.

There’s a full-page excerpt from Julian Gough’s recently published Kindle Single Crash! How I Lost a Hundred Billion and Found True Love, honorary Irish writer Molly McCloskey reviews a new book of essays on artists and writers by Janet Malcolm, Gabriel Byrne reviews Roddy Doyle’s new novel The Guts and there’s an extensive interview with Doyle himself by Patrick Freyne.